The Death of Weed Culture

If you live in a state like California, it’s hard to remember a time when weed was actually illegal. Classified as a misdemeanor in 1975, made “medically” legal in 1996, and recreationally legal in 2016, anyone under the age of 40 would be hard-pressed to recall a time when possessing a gram or two felt like a real risk. This trend is common in states around the country. Twenty-four states have legalized marijuana for recreational use, and forty have legalized it for medical use. It feels like only a matter of time until weed is federally legalized.

Overall, legalizing weed seems to be a good thing: fewer unnecessary incarcerations, increased state revenue and opportunities for economic growth, and an overall increase in safety. However, legalization has come at a cost. Specifically, the corporatization and death of weed culture.

Weed as Rebellion

There was a time when smoking weed was an act of rebellion. Born from the countercultural movement of the 1960s, marijuana use was associated with the revolutionaries of the era. America had been thrust into “reefer madness” at the beginning of the 20th century, largely due to the association the drug had with Mexican immigrants during the Depression era. Those in power falsely claimed that weed would make you lose your mind, commit crimes, and act as a gateway to harder drugs.

Smoking pot in the 1960s defied these conventions. Weed did not make you a criminal or destroy your mind (at least not for more than a couple of hours). Instead, it became symbolic of the movement at large: the rigid conventions of the ’40s and ’50s were bullshit, and people needed to think differently.

The weed during those days sucked. It’s funny that modern weed culture was born at a time when you were smoking more seeds and stems than actual bud. But nonetheless, the foundation was laid, and an entirely new subculture grew from this initial revolution.

The Evolution of Weed Culture

Over the next few decades, weed culture evolved. From Cheech and Chong to Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, weed culture came to encompass a diverse set of people and tastes. This diversity was reflected in the wide variety of music genres that were weed-centric: rap, reggae, stoner rock, psychedelia, jam bands, white-guy reggae, punk, even heavy metal. Uniting this wide cross-section of society were two central tenets:

- A love of weed

- The call to legalize it

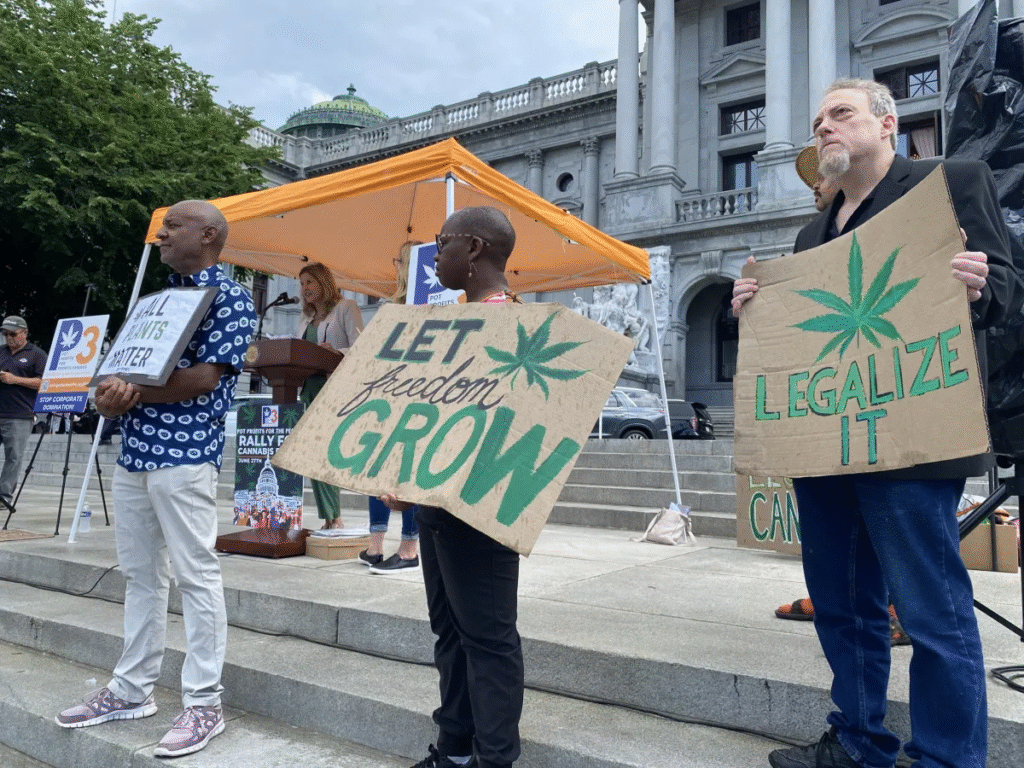

Up until the early 2010s, the call to “legalize it” retained a grassroots, countercultural aura. Smoking weed was simply harder to do back then. You had to go to an actual drug dealer and buy what was essentially mystery weed.

When Colorado and Washington legalized weed in 2012, the floodgates opened. The corporatization of weed had begun. At first, legalization was a unifying event for weed culture—it meant victory in two states. But soon, corporate interest was piqued. Weed became an investment opportunity. Blue Dream was no longer a rare treat from a local dealer; it was just one of a hundred options in a dispensary, pitched to you by a budtender as a decent budget pick.

Weed Culture Without the Cause

The dream of legalization still has a long way to go. Weed is still illegal in many states, and it remains illegal under federal law. But federal legalization now feels inevitable (see: Canada). As the calls to “legalize it” weaken in states like California and Colorado, weed culture is beginning to lose one of its central tenets.

Without the unifying rallying cry, all that’s left is the love of the drug. And that, on its own, is odd. There is no “alcohol culture” that would be considered cool and not deeply sad. The idea of a “meth culture” sounds insane. Unlike these other substances, weed culture persisted because of its link to counterculture. Without that association, it becomes just a group of people who like to get high. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it lacks purpose.

When Weed Lost Its Cool

In only a few years, weed has gone from counterculture to popular culture. Walk into any dispensary and you’re overwhelmed by low-dose edibles masquerading as “wellness products.” Companies now market weed to groups that would have been considered narcs twenty years ago. People over 55 and parents are now consuming marijuana for fun.

It’s the oldest story in the book: once your parents start doing something, it’s no longer cool. Something doesn’t have to be cool to be good, but when a culture is predicated on being cool, losing that cool means losing its identity.

The Arms Race for Potency

Legalization has also fueled an arms race to produce the most potent weed. Modern flower can hit THC levels of 30%, and concentrates can reach up to 90%. Gone is the 1% THC brick weed of the ’60s and ’70s, the kind you could smoke indefinitely for just a slight buzz.

That weed sucked, but it produced the mellow high that gave us the archetypal stoner, immortalized by characters like Spicoli, Slater, and Shaggy. For the uninitiated, modern weed hits like a ton of bricks. Even seasoned stoners can find themselves white knuckling a journey through their psyche after a hot dab.

The gear has escalated too: scientific glass, artisanal rigs, high-tech vaporizers. All of it a far cry from a simple joint. This high-powered weed and its many delivery methods have allowed stoners to nerd out, spending thousands chasing ever-slight variations of the same high. Naturally, with these new strains and methods big business has found new ways to extract even more money from consumers.

The End of Weed Culture?

The fight for national legalization is far from over, but it feels closer every day. As the calls for legalization fade, the countercultural edge of weed culture fades with it. Maybe there isn’t much harm in that, but honestly, it’s made weed culture kind of annoying.

It’s no longer cool to make smoking weed a personality trait. At its core, getting baked is the same as it ever was—just with way more intensity thanks to stronger weed. But today’s weed culture is not the same as the culture of the past fifty years. It’s lost its edge and gone corporate.

Maybe that was the goal all along. But there’s no denying the shift of the last decade.

Leave a Reply