5. Thanos – Avengers: Infinity War (2018)

The initial run of Marvel movies leading up to 2018 had a villain problem. These early movies were great at establishing our heroes and developing an interconnected world. However, I felt these initial movies lacked compelling villains. With the exception of Loki (who ultimately had a redemption arc), the villains often felt one-dimensional in their villainous plots. Thanos and Killmonger, both introduced in 2018, broke from the mold of the traditional Marvel villain. These characters had motivations that were understandable, and one could make an argument for their ultimate goals.

Thanos wants to restore order to the universe. His solution? Wipe out half of the existing population. While this plan is a bit extreme, Thanos brings to light an important issue in our own world – man-made degradation of the environment. Climate change and the general loss of biodiversity around the globe are all rooted in human causes. Wiping out half of the population probably would go a long way in restoring Earth to its natural state. While I don’t condone turning 50% of the population into dust, Thanos’s goal – restoring order – isn’t necessarily rooted in a general evilness. Thanos’s desire to restore order in the universe is somewhat noble. He may be going about the solution in the wrong way, but I can relate to his concerns about the human impact on the planet.

4. (Tie) The Vampires – Sinners (2025) / The Vampires – The Lost Boys (1987)

Sinners and The Lost Boys both feature packs of vampires that offer an alluring argument to join the “dark side.” Unlike traditional, decrepit vampires like Nosferatu, these vampires are sexy. To a complete outsider unfamiliar with the dark ways of the vampire, the lives these creatures live seem pretty cool. Eternal youth, magic powers, and a built-in community of like-minded individuals – what’s not to like?

The Lost Boys was one of the first movies to introduce the cool vampire. Despite the thick lacquer of ’80s clichés, these vampires are objectively cool. Layered in sweet leather outfits with massive hairdos, the Lost Boys seem like a fun – but dangerous – hang. Joining the Lost Boys crew is an invitation to be young forever, riding motorcycles on the beach and jumping off bridges just for the hell of it. Guys this cool don’t go out in the daytime anyway, so who cares if the sun will kill you? For a troubled teenager looking to fit in, this group of vampires is extremely compelling.

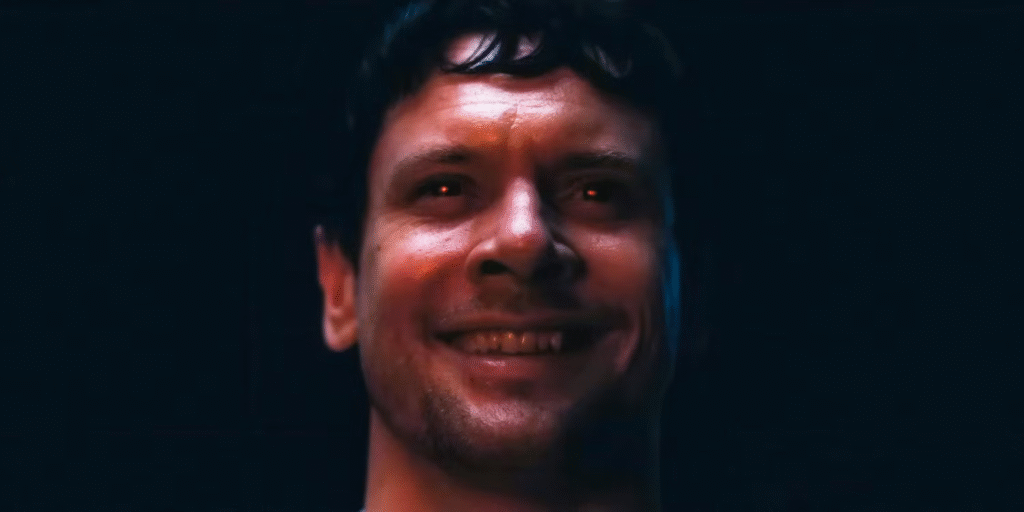

Sinners also features a group of ageless vampires looking to recruit fresh blood into their vampire clique. However, the vampires in Sinners offer a more nuanced and less vapid argument for joining their ranks. They offer equality and acceptance during a time when those things were hard to come by for non-WASPs. Above the traditional vampire tropes of agelessness and mystical powers, these vampires offer freedom from the societal constructs designed to oppress non-white Americans. That’s not to say these vampires aren’t cool. At the end of the movie, vampire Michael B. Jordan and Hailee Steinfeld look like the coolest people in the ’90s.

In both films, we learn that the price of vampirism is losing one’s soul. Regardless of the reasons behind becoming a vampire, the common theme is that one needs to sacrifice their soul to become one. Is living forever, equality, or a sweet hairdo worth losing your soul over? I’d argue probably not. However, people are willing to sell their soul for much less in return, so I can’t deny the arguments these vampires are making.

3. Willy Wonka – Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Some people may take offense to Willy Wonka’s inclusion on this list as a “villain.” As depicted in the 1971 film by Gene Wilder, he is borderline evil. Colonizing Oompa Loompas for labor, (probably) killing children, and subjecting people to the “tunnel of terror.” At the very least, Willy Wonka is an unhinged vigilante for misbehaved children… and a colonizer.

There is a method to Mr. Wonka’s madness. By subjecting the children to the tunnel of terror and the dangers of the chocolate factory, Willy is trying to find who is cut out to run the chocolate factory. While drowning a fat kid in chocolate might be an extreme way to teach a lesson on self-control, Augustus might think twice next time he picks up the candy. Willy’s factory is the ultimate contradiction – designed to bring wonder and joy to children while simultaneously being a death trap for children. The factory is just like the business – on the surface, it may seem designed for children, but in reality, one needs to withhold from childlike urges to successfully navigate it.

Why choose a young child to take over the reins of a candy empire? That’s where Willy’s plan starts to run thin. Maybe the competition should have been geared toward young adults instead. It seems a little unfair to lure little kids into heaven on Earth only to take them out one by one. But, as the tunnel of terror shows us, Willy is a little zany and has his own methods of doing things.

2. Neil McCauley – Heat (1995)

Michael Mann’s Heat is an all-time classic. Part of what makes it a classic is the interplay between the two leads. Neil McCauley and Vincent Hanna are two absolute forces fated to collide in 1990s Los Angeles. Neil is objectively the villain here – he kills cops, robs banks, and lives by a semi-monastic code that doesn’t lend itself to being a reliable guy. However, it’s hard not to root for him. Like Vincent Hanna, he lives by a code; in another life, he and Vincent could have occupied opposite roles. “Two sides of the same coin,” as they say.

Neil is good at what he does. The first heist makes it clear that he is a professional, adhering to a strict set of rules he has developed over years of trial and error. If Neil worked on Wall Street or in the C-suite of a startup company, he probably would have made the Forbes 500. It just so happens that Neil’s craft is robbing banks. Neil doesn’t want to kill anyone, nor does he want to rob Joe Schmo off the street. He’s after the bank’s money. If it wasn’t for Waingro losing his shit, Neil may not have had to kill anyone. While I don’t condone wanton murder, I respect Neil for being the best of the best. Neil is right about leaving everything behind if the heat is coming around the corner – in order to be the best, you have to dedicate your whole life to being the best. No one can get in the way. People adore Michael Jordan for essentially embodying this mantra during his run in the ’90s. Why not respect Neil? He ultimately proves his own thesis when he is killed in the end for failing to abide by his own credo. Even when breaking with his own ideology, he does it for the right reasons (killing Waingro). Neil may be a criminal, but he is one of the best to ever do it.

1. Roy Batty – Blade Runner (1982)

I’m certain Blade Runner would not be considered one of the all-time great science fiction movies without Roy Batty. Harrison Ford gives a career-best performance as Deckard, but Rutger Hauer steals the movie as Roy in the closing scene. Unlike a lot of movie villains, we feel a profound sense of loss when Roy ultimately perishes. Moreover, Roy made beach blonde hair seem like a viable hairdo.

Blade Runner asks us to interrogate what makes us human. The murderous replicant Roy first appears to be a horrifying argument against artificial intelligence. A machine with superhuman abilities gone rogue, Roy will stop at nothing to exact revenge against his creators. By the end of the film, we realize that Roy’s actions are simply products of the human condition. Roy wants to be free, and he doesn’t want to die. These two traits are probably the most universally shared among all human beings. Roy ultimately redeems himself, saving Deckard in the climactic rooftop chase. Grappling with his mortality, he laments all that will be lost with his death – his memories. These memories remind us that he, like any other human, experienced life as an individual. All life boils down to is experiencing our surroundings, making Roy extremely relatable in his final moments. He is the most sympathetic villain in movie history.

Leave a Reply